My sermon on Prayer for Advent’s Common Ground service, last Thursday (January 24). Not my best. Finished it right before the service started; could have used one more day of editing, I think.

My sermon on Prayer for Advent’s Common Ground service, last Thursday (January 24). Not my best. Finished it right before the service started; could have used one more day of editing, I think.

The readings were from 1 Samuel 1:1-2;9-18 (Hannah and Eli) and Luke 11:1-4 (the Lord’s Prayer).

**************

I’ll admit that when I first saw the schedule for Common Ground this season, and I saw I was ending this first term with a message on Prayer ‚Äì I got a little excited. And then I thought about it a little more….and I got a little less excited. Because prayer ‚Äì it’s so big. Where do I even start? Better yet, what can I say? And if I can’t say anything about prayer ‚Äì and I’m a full time, professional, pray-er ‚Äì should we maybe just sit here, quietly, for 10 minutes ‚Äì and that be it? It would make it the shortest message I’ve ever had to write.

Or…maybe I could go all theological (I’m a seminarian after all) – and say that as Christians, it is our job to pray; that’s stamped right in the job description, right next to love God, and love your neighbor. We’re called to pray ‚Äì to talk to, and with, God. We’re called to not be afraid of our vision of God ‚Äì be it an old man in a white beard, a ghost like spirit, or a being so distant that it cannot be seen ‚Äì and we’re called to take that vision of God ‚Äì a vision that will always be incomplete and inadequate ‚Äì and talk to it. Talk to God. Listen to God ‚Äì and engage God in a mutual relationship of actual communication.

But… I dunno ‚Äì when it comes to prayer, sometimes, when I do it, it feels like when I’m trying to talk to my cat. She’s this 9 lb, gray tabby, with white paws, who is the nicest cat in the world ‚Äì but when I try to talk to her, she looks at me for a second, then turns around, ignores me, and starts cleaning herself ‚Äì falls asleep ‚Äì stalks the dog. Basically, unless what I’m talking about involves putting food into her dish, she just doesn’t care. I can talk all I want at her ‚Äì but unless I say the right things, or push the right buttons, or use the can opener, she just isn’t going to pay attention to me. My words and tone don’t work ‚Äì they’re too irreverent for her ‚Äì so why would she listen to me?

And I think it’s easy to look at prayer to God like some kind of checklist ‚Äì where certain rules have to be followed for it to work. I mean, just look at physically how we pray. We put our hands together just so, one next to the other, with fingers tight together, and hands pointing up ‚Äì like there’s some kind of laser beam that directly shoots up the prayer to God. But if that’s seems a tad too, pious, we can also fold our fingers together like so. That seems a little less ‚Äì rigid. Oh ‚Äì and there’s the head. Sometimes our eyes are closed, other times, our head is looking up, or straight a head, or down. And if we’re looking down, our hands might not be folded at all ‚Äì but will be placed one on top of the other, hanging down at our hips, in the popular “fig leaf” position. And if a pastor is praying, we might assume the old prayer position of the early church ‚Äì with our arms out, palms turned up ‚Äì kinda like a TV antenna or the beginning of a strange hug with the sky. Or we might kneel and fold our hands. On the hard floor like we have at Advent ‚Äì there’s a physicality to it ‚Äì it feels solid, like we’ve done something, and when our joints pop as we get up, we feel like we really just did something. We really just prayed.

So prayer can feel like it has a certain song and dance to it ‚Äì a song and dance that we need to get right ‚Äì or else we won’t pray the right prayers or they won’t be heard as well as they could be.

And then there are the words. Or the lack of words. There’s silent prayer ‚Äì but that’s never really worked for me. When I try to pray silently, I find myself trying to get the right pose ‚Äì and then thinking about the work I have to do, or what I need to buy from the store, or how long I have to keep silently praying for…

So lets focus on the words. And just like there seems to be a right way to physically hold ourselves when we pray ‚Äì there sometimes seems to be a right way to pray too. And even a “prayer-professional” like me, I am amazed at how intimidating prayer is.

Because one of the great things about Advent on Sundays is our prayers. They’re prepared by Pastor Lundblad most Sundays ‚Äì and if she can’t create them, we turn to other resources ‚Äì like the resources put out by the ELCA ‚Äì and use those. And these are gorgeous, beautiful, powerful, wonderful prayers. Prayers that have life, depth, meaning. Prayers that touch the entire world. Prayers that are mini-psalms themselves. And when the Assisting Minister prays those prayers ‚Äì I mean ‚Äì it feels like we’ve prayed the heck out of those prayers, doesn’t it? Like, you want to high five someone afterwards or bump chests ‚Äì like YEAH ‚Äì we got that one! We prayed that prayer. God is totally going to listen to that one.

And then, you might go home, and you have your own prayer routine of praying before you fall asleep at night, and….your prayers just don’t sound right. My prayers don’t sound right. They’re…weak, not as pretty. They seem mundane or just plain silly. On Sundays, we’ll pray for the safety of the people of Syria ‚Äì and that seems so much more important than laying in bed, praying that we won’t sleep through our alarm again because we’ve been late twice already this week and the boss noticed. The words on our lips, or in our head, just seem small…or petty…or even if we try to pray those giant prayers alone, we seem too small for them. Too weak. Too quiet. Those prayers just don’t seem to fit in the small bedrooms of our tiny New York City apartments.

So, our routine weakens. We start sleeping through our own prayers instead of just our alarm ‚Äì and we stop praying because the big prayers of this assembly seem to cover it ‚Äì and their beauty has made us small ‚Äì has made us physically withdraw from the act of prayer ‚Äì because we couldn’t just get our words, reflection, mediation, just right. We stop the mutual relationship because we just feel like we’re not good enough.

And this totally makes sense ‚Äì this idea of being too irreverent, too insignificant, to pray. We might not be able to call it that ‚Äì but I think that’s a good label. I mean, the creator of the universe, the God with the power to flood the earth and dry it out again, the God who rescued Israel from slavery, who sent Jesus to hang with outcasts and eat with the unwanted ‚Äì who died one of the most painful deaths that the Romans could throw at him ‚Äì and Jesus still came back, raised from the dead ‚Äì who still comes down to be involved in our lives, to walk with us, to see how exactly irreverent we are ‚Äì that’s incredibly intimidating. That’s why I love this story from Luke ‚Äì one of the places where we get our Lord’s Prayer from. The disciples come on up and ask Jesus, while he’s praying, how they should pray. Of course we want to see how Jesus prayers; what he says. He’s got some fast path method of talking to God ‚Äì we want to copy. And we do, every time we celebrate the Eucharist. But the disciples asked pre-cross, pre-death, pre-resurrection, pre-Jesus sitting at the whole right hand of God thing, you know, being scarily perfect. Jesus’ prayer can seem like it is for the perfect ‚Äì for those who will go to the cross. But we’re not ‚Äì and we might not want to to go there.

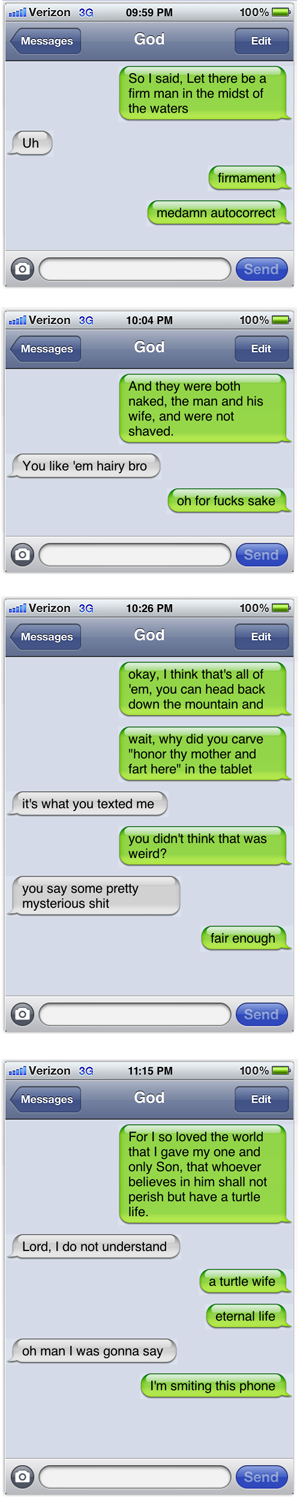

And, Lord knows, our prayers are imperfect. As a new professional pray-er, I’ve had lots of fun with being the guy called to pray ‚Äì and, I’ve been as irreverent or ridiculous as they come. I’ve prayed for the wrong things ‚Äì like, when I’m a meeting of my internship committee, I’ll pray for the building ‚Äì though, well, that’s suppose to be for the property committee. And I’ve done that thing where my prayer gets completely confused and rambles for what feels like hours ‚Äì when I just pray, and pray, and pray, and I feel like I need to get to an end but this isn’t it so I just keep going ‚Äì and this happened while people were waiting to devour their donuts and coffee during fellowship ‚Äì and their bellies were actively growling before I finally ended it in a completely unsatisfactory place. And I’ve done this in public! In front of people! I’ve prayed prayers that felt so unsatisfactory, that I was actively embarrassed about ‚Äì prayers that I wished I hadn’t prayed. And the feedback ‚Äì it’s always terrible, when you pray, to hear “well, next time, you’ll do better.”

But the funny thing is that, even though this keeps happening, I keep getting asked to pray. And I keep praying ‚Äì out loud ‚Äì in different ways ‚Äì in different ways that feels irreverent, to me ‚Äì but people keep asking me to do it ‚Äì and I know I’m getting “better” at it ‚Äì but I keep praying, keep feeling embarrassed, because the thing about prayer is that it truly matters.

I like this story of Hannah from 1 Samuel a lot. I think it speaks volumes about prayer. She’s in a tough spot. She’s childless and she wants that to change. That…that’s seems like a bigger, deeper request, than the prayers I say ‚Äì like, today, while waiting in the cold, and praying that God sends the A train sooner rather than later ‚Äì but what I love about this story is that she’s by the temple, presenting herself before God, being reverent ‚Äì but does this completely irreverent thing. She’s praying, silently, and moving her mouth. She’s doing a completely normal thing to us ‚Äì if you watch me, or each other, during the prayers for intercession in services ‚Äì you will see mouths move ‚Äì but right then, she’s praying, and doing something that causes a priest of God to look at her and call her out for behaving like she’s drunk. It’s brilliant! She’s praying, hard, faithfully, like she should ‚Äì and a priest of God is seeing her, sees her as being irreverent, and immediately assumes she’s drunk. But she stands her ground and says ‚Äì no ‚Äì I am praying, right here, right now. And that this prayer matters even if it looks like I am being irreverent or not polite. This prayer matters. And the priest, Eli, immediately gets it, and prays for her. He affirms her ‚Äì even though he does not know what she prayed. He just affirms it. And Hannah, that’s what she needed. She needed to feel, to know, that her prayer was heard. What mattered wasn’t that it was answered (though we know it will be), but that she actually prayed ‚Äì in her way ‚Äì and that the professional pray-er – that they affirm the truth ‚Äì the hard truth that even I struggle with ‚Äì that even the irreverent prayers, even the prayers that embarrass me, even the prayers that I screw up delivering ‚Äì they are heard. That God listens. That Jesus, who walks with us as we go through our lives ‚Äì even if we don’t feel his presence right now ‚Äì that he’s actually paying attention to us. And that the right way to pray is to just pray. Let it all hang out. Be bold enough to be like Hannah ‚Äì to be called irreverent but know that you are praying; that you are working on your relationship with God; that you are being heard and listened to ‚Äì because that’s God’s promise to each and every one of us.

In a minute, we’re going to do an activity. The first one is, well, when Dan and I were emailing back and forth about this service ‚Äì I realized that, when it comes to prayers, I actually read a lot of prayers, but they really only come from one source. How many of you are on twitter? I know some of you are. I know some of you follow me. And, if you do, every once in awhile, you’ll see me retweet some small prayers, prayers that are 140 characters or less, from the Unvirtuous Abbey. I love their tagline: “Holier than thou, but not by much. Digital monks praying for people with first world problems. From our keyboard to God’s ears.” These are folks using pop culture and social media to pray ‚Äì truly pray. They are sometimes completely irreverent, like when they re-tweeted “For the gift of discernment between blue socks and black, Lord, we give thee thanks.” Or, another one, that I can totally relate to: “From those who have leaking headphones while commuting, Lord deliver us.” But they’re also willing to take chances ‚Äì to be engaged with the culture and what matters around them. And they get in trouble for it ‚Äì like, just today, when they tweeted “For those who claim to be pro-life yet oppose stricter gun control, we pray to the Lord” or when they re-tweeted “Prince of Peace, when in situations of conflict, may your Church be agents of peace and no longer accomplices in violence.” However you stand on these issues, they are prayers ‚Äì solid prayers ‚Äì prayers that, in 140 characters, speak volumes.

So, I would like you all now, to write your own prayers, of 140 characters or less. The boxes on the page are 140 characters long ‚Äì so you’ll have to make sure you don’t go over. And, then, during the next activity, Im’ going to compile some of these into our prayers for intercession.

If you haven’t yet, please go pickup a copy of this month’s

If you haven’t yet, please go pickup a copy of this month’s

My sermon on Prayer for

My sermon on Prayer for

Yesterday, I assisted in a funeral, and, for the first time, it was a funeral for someone I knew.

Yesterday, I assisted in a funeral, and, for the first time, it was a funeral for someone I knew.